Model View Controller on iOS

I’m currently writing a book on iOS app architecture, to address a problem that many beginning – and even experienced! – app developers struggle with:

How do you decide which objects you need?

How you make those objects talk to each other?

And how do you prevent your code from becoming a mess?

Of course, the infamous MVC pattern makes an appearance too.

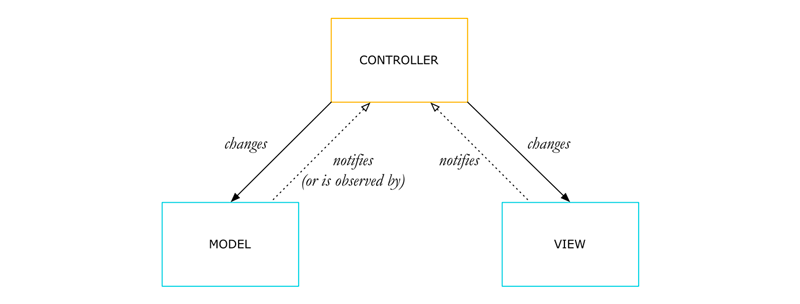

This is the theoretical picture of how Model-View-Controller is used on iOS:

All the communication between the model and view objects goes through the controller, so that the model and view are unaware of each other’s existence.

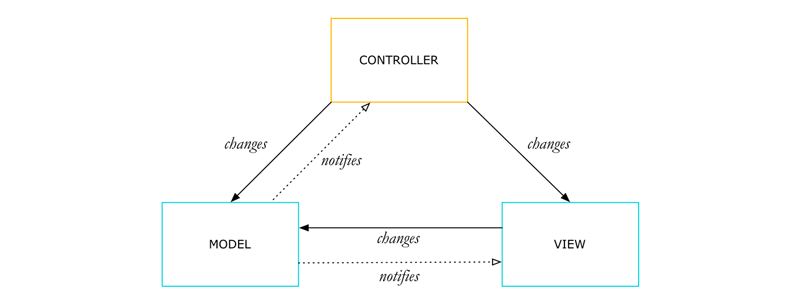

On the other hand, this is what MVC looks like in Smalltalk:

They are not the same! Smalltalk’s controller and view are very different from Cocoa’s controller and view. If you see someone explain MVC on iOS using this picture, then they’re talking about the wrong thing. (Note: In web frameworks, MVC is something completely different again.)

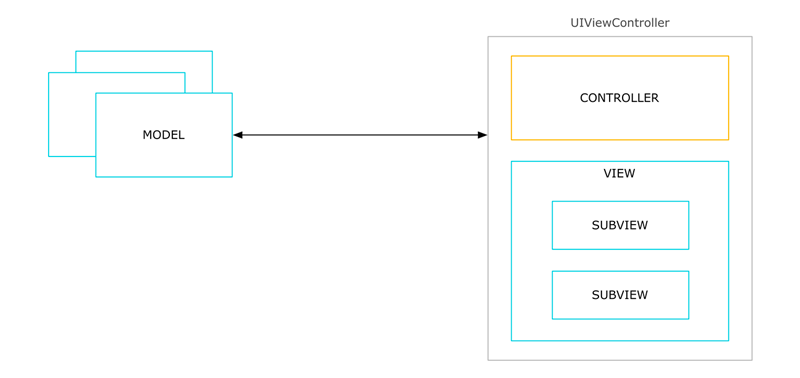

So much for the theory. Here’s how you’re probably using MVC in practice:

Contrary to popular belief, the UIViewController is not just the controller; it’s also responsible for the view. That’s why it has both “view” and “controller” in its name. In fact, the view controller doesn’t just have a single view, but owns and manages an entire hierarchy of views and subviews.

This picture is quite different from the theoretical MVC. Instead of having one model, one controller, and one view object, the controller and view roles are now combined into a single object, the UIViewController. And while there usually is more than one view, there’s still only one controller.

Many of the subviews will want to talk to their own model objects. As a result, the controller part often ends up coordinating between multiple model objects and multiple views. This leads to the problem of Massive View Controller, where the UIViewController tries to do way too much.

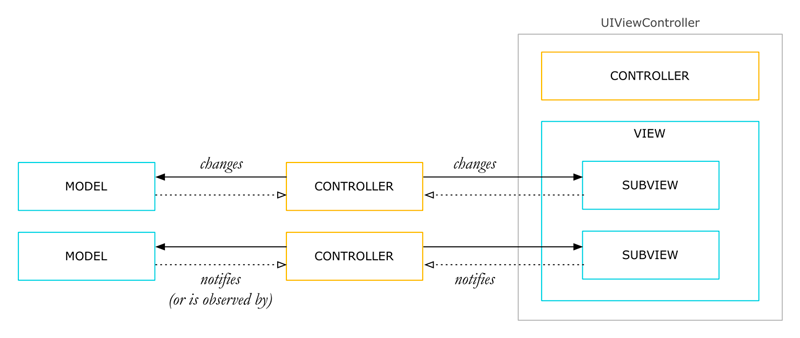

To clean up the mess, you can do something like this instead:

This is still MVC. I’d even claim it’s closer to the ideal of MVC than the previous situation. Just because you have something called a “view controller” doesn’t mean it needs to sit between all your model and view objects. It’s often cleaner to give different model and view objects their own controllers.

This approach is more common on OS X where you can set up so-called bindings between your models and views; each binding uses its own controller object behind the scenes. But there’s no reason you can’t use such additional controllers on iOS… you just have to roll your own.

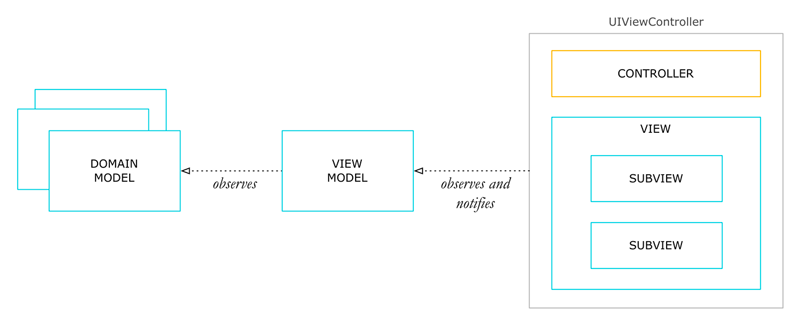

The above is very similar to the alternative pattern, Model-View-ViewModel or MVVM:

In MVVM, there is still an object between the model and UIViewController but it is not another controller; it’s something called a view-model.

Now you have two types of models: 1) the domain model, which is where the app’s main data goes, and 2) the view model, which contains the data that should go into the views.

Here’s the difference between using MVC and MVVM:

When a controller is notified of a change in the model, it sends a message to the view and gives it new data to display. So the controller is tightly coupled with the view, making it hard to unit test in isolation (among other things).

A view-model, however, never directly sends a message to the view. It doesn’t even know the view exists. Instead, the view-model takes the domain model’s data and converts it into content for the views. The views then observe these changes in the view-model and redraw themselves with the data from the view-model.

One can argue that MVVM is the more object-oriented solution because the view-model is a real thing with logic and state, while the controller is merely procedural logic wrapped into an object.